What is multiplexing?

With the advances in sequencing technologies, it is now possible to sequences 1000s of Gigabases of data on a single flowcell (NovaSeq). This is much more data than is actually required for a sample when performing many common bioinformatic analyses. To better utilize this massive amount of sequencing data, it is possible to run multiple samples after library preparation in a single lane. Running multiple libraries in a single sequencing lane is called multiplexing. The decision to multiplex must occur prior to library preparation.

In order to do this, there has to be a way to track which read came from which library. This is done by attaching 8-10 bases to the end of all sequences from the same library. These barcodes/indexes are unique between samples allowing for downstream splitting of the sequences after sequencing.

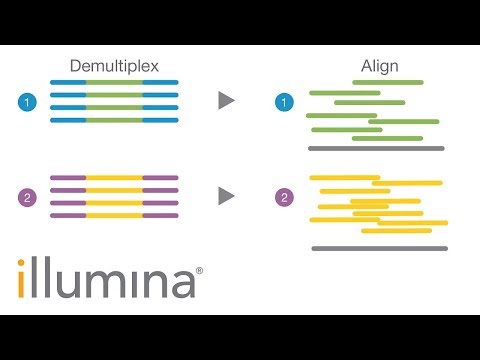

The barcoded libraries are pooled and run on a single sequencing lane. The sequencing data is demultiplexed using the barcodes to identify which reads originated from which samples. Demultiplexing is a computational step usually performed by the sequencing centre.

Why do you need to multiplex?

If one is sequencing many samples, using a single lane to run each sample or library is not economical and sequencing resources will be used inefficiently. Further, there is some technical variation between sequencing lanes called the sequencing lane effect. If each sample is run on a different lane, the lane effect will be compounded with sample. Appropriate multiplexing is recommended in order to avoid the technical bias of lane effects.

How do you multiplex?

During multiplexing the experimental design principles of randomization and blocking need to be applied. The idea is to have every group in the experiment represented in every lane being used for sequencing. Another way to think about this is to try to place only replicates in separate lanes.

Say, we have one control group A and two experimental groups, B and C in our experiment. We have six replicates in each group. In total, there are 18 samples to be run. Depending on the platform and experimental considerations, we may be able to multiplex all samples on the same lane.

How not to multiplex an experiment.

Let’s assume we want to run only 6 samples per lane in our experiment we designed above. If we run it this way.

- 6 replicates of group A in lane 1

- 6 replicates of group B in lane 2

- 6 replicates of group C in lane 3

Lane effects would be introduced and would be confounded with treatment group. We wouldn’t be able say that the differences we saw were due to treatement group or lane effect (confounded).

How you should multiplex an experiment.

A better design would be

- 2 replicates of group A, 2 replicates of group B, 2 replicates of group C in lane 1

- 2 replicates of group A, 2 replicates of group B, 2 replicates of group C in lane 2

- 2 replicates of group A, 2 replicates of group B, 2 replicates of group C in lane 3

In this way, all the groups have been run on all the lanes used for the experiment, in effect, cancelling out lane effects. This also works because there are an even number of replicates spread across all the lanes.

Ultimately the decision to multiplex or run samples separately and when multiplexing, how many samples will be multiplexed depends on the amount of biological variation in the samples and the need or not for sequencing depth. The effect of variable sequencing depth on the consistent and sensitive detection of gene expression signatures has been studied.

Studies have shown that unless you are specifically looking at differential splice variant expression, more replicates is better than more depth. RNA-seq differential expression studies: more sequence or more replication? 2014

So how does one know which read is coming from which sample?

During library preparation, a small index sequence, also called the barcode, is introduced into every DNA or cDNA molecule by including it in the primer sequence. There are different types of indexing:

Single indexing: a single index sequence is introduced to one end of every molecule in the library. The index is unique to the library/sample. Single indexing can only be used in the absence of multiplexing. The sequencing lane and index combination helps identify the samples from which the sequencing reads originated.

Combinatorial dual indexing: two index sequences are introduced at either end of the molecules in the library. But the indexes are not unique to the sample- their combination is. So index X1 may be common to two libraries, A and B and index X2 to the libraries, A and C. But the combination of barcodes X1 and X2 is unique and found only in molecules from library A. Combinatorial indexing was designed for multiplexing. The drawback is that loss of a single index out of the two will lead to ambiguity and the reads cannot be assigned to a single sample.

Unique dual indexing: unique indexes are introduced at either end of the library molecules. None of the barcodes or indexes are shared between libraries. This is recommended for multiplexing.

The terms index and barcode will be used synonymously in this chapter. Similarly, index hopping and barcode swapping.

The sample misassignment problem with Illumina, What is it and how do I avoid it.

Sample misassignment occurs when one sample erroneously gets the barcode for another one. Some of the reads that belong to sample A are incorrectly attributed to sample B and, this, cannot be resolved computationally.

How does sample misassignment occur?

A sample may get the wrong barcode sequence due to

- Cross-contaminated oligo barcode preparations

- Index hopping during library preparation

- Index hopping during sequence cluster generation

- Sequencing errors affecting the index sequence

- Samples from previous runs contaminating the lane

- During multiplexing on the Illumina platform, sometimes the barcode can switch for sequencing reads from one cluster to that of another one that is close by but is sequencing molecules from a different library. This is called “sample bleeding”.

- Overclustering can increase the possibility of sample bleeding. And this phenomenon may be occurring at a low, negligible frequency in the older clustering chemistries using bridge amplification.

In the bridge amplification-based Ilumina sequencers, hybridization of library molecules to template oligos immobilized on the flow cell would be followed by a wash step. This would ensure removal of extra free molecules like adaptors etc. in solution before sequencing (bridge amplification) began. The newer Illumina platforms like HiSeq 3000 and HiSeq 4000, HiSeq X and NovaSeq 6000 use the patterned flow cell technology. To ramp up throughput, the separation between the hybridization and the sequencing amplification steps was removed and, a new patented ExAmp polymerase with superior amplification capabilities was introduced. These features also increased the chances of index hopping, even with small amounts of free adaptors, compared to the older bridge chemistries. [https://www.genomeweb.com/sequencing/study-reports-incorrect-assignment-reads-samples-multiplexed-illumina-hiseq-4000#.XBnVGc8zbs0 , http://enseqlopedia.com/2016/12/index-mis-assignment-between-samples-on-hiseq-4000-and-x-ten/]

How big a problem is sample misassignment due to index hopping?

The frequency of misassignment is much higher than in conventional bridge amplification clustering. The rate of misassignment has been variously reported to be <1% to 7%. A recent study using HiSeqX, HiSeq 4000/3000, and NovaSeq reported sample swapping rates from 0.2 to 6% [https://bmcgenomics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12864-018-4703-0]. Another study reports that 5-10% of sequencing reads are misassigned on the newer machines [https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/04/09/125724], while another study finds no evidence of index switching in the HiSeq X [https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/05/25/142356].

Transcriptomic studies may not be seriously affected if one is not looking at low frequency transcripts. But without knowing the actual degree of misassignment and the proportion of samples and transcripts affected in one’s study, it is advisable to take precautions.

For some applications, like identifying clinically relevant rare sequence variants, profiling of somatic variants in cancer, metagenomic studies and detection of low titer microbes or viruses in samples, there is extremely low tolerance for these events. The problem can be compounded, if the variants are located in regions like repeats that need high sequencing depth. Moreover, if clinical decision making or genetic counseling is seriously affected by the low frequency allelic variant identification, misidentification or non-identification, then there may be zero tolerance for even the lowest rate of sample misassignment.

This video describes index hopping and ways to minimize it.

- Library purity – remove any free adaptors

- Library storage – stored individually not pooled

- Library prep methods – PCR-Free libraries show higher hopping levels compared to other preps

How to address sample misassignment?

During library prep

- Verify the sequences of barcodes on the purchased oligos before library preparation. This is to confirm that there is no barcode contamination originating from the oligo synthesis or purification process itself.

- Avoid barcode contamination during various pipetting or library amplification steps.

- Ensure the removal of all excess, free adaptor after library preparation to minimise index hopping during sequencing.

- Illumina recommends storing individual or pooled libraries at -20 C not 4 C if they are not to be sequenced immediately. Pool immediately before sequencing or sequence as soon as you pool rather than storing pooled samples.

During demultiplexing

Taking into account the Q-score of indexes when demultiplexing may help avoid misassigments due to sequencing errors in the index region. For example, discard reads with Q-score less than 30 for the index reads.

While multiplexing on platforms using patterned flow cells

-

Do not use combinatorial dual indexed barcodes. Unique dual indexes are available from several providers including IDT, Illumina TruSeq UD Indexes, the NEXTflex Dual-Indexed DNA Barcodes from Perkin Elmer etc.

-

Avoid the use of PCR-free, ligation based library prep kits in conjunction with patterned flow cell based sequencing. These samples tend to have more free adaptor that contribute to index hopping.

-

On the HiSeq X, sequence a single 30X whole genome on a single lane.

-

Pool similiar libraries together so that dominantly expressed transcripts are unlikely to lead to index hopping with other samples. For instance, multiplex brain samples separately from liver samples. Do not mix different organs, species etc. together. However, this needs a priori knowledge of expression profiles of samples and is discordant with strategies used to address sequencing batch (lane) effects. Also if comparisons between tissues are to be made then this strategy is not possible due to confounding with lane effects as described above.

-

Illumina recommends that RNASeq and CHIPSeq libraries should not be multiplexed together even on non-patterned flow cells. This is because, CHIPSeq will have enriched sequence that can cause sample bleeding into RNASeq samples. (ie don’t mix experiment types) [https://www.illumina.com/science/education/minimizing-index-hopping.html]