Introduction to Bioinformatics

Preface

The best way to learn bioinformatics is through examples of real world problems. The Bioinformatics Workbook provides the reader with an in depth understanding of experimental design, data acquisition, data wrangling, data analysis and visualization. This is accomplished through worked out example problem in each of these sections along with one or more advanced problem sets and corresponding solutions. This books assumes that the reader has some knowledge of biology and basic understanding of the Unix command line. However, for the beginner, the appendix contains introductory material and tips/tricks for common bioinformatic problems, that is referred to for more information throughout the book.

What is Bioinformatics?

Bioinformatics is the study of biology using information. It involves the acquisition, storing, processing and visualizing of biological data. The most common form of biological data is generated from high throughput sequencing machines that are produced by companies such as Illumina, Pacbio and Nanopore. However, biological data involves so much more beyond genomics. Other biological data types include but are not limited to data generated for proteomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics, epigenetics and lipidomics. It also includes the metadata of the sample: tissue type, location collected, time collected and phenotype.

Why do we need more bioinformaticians?

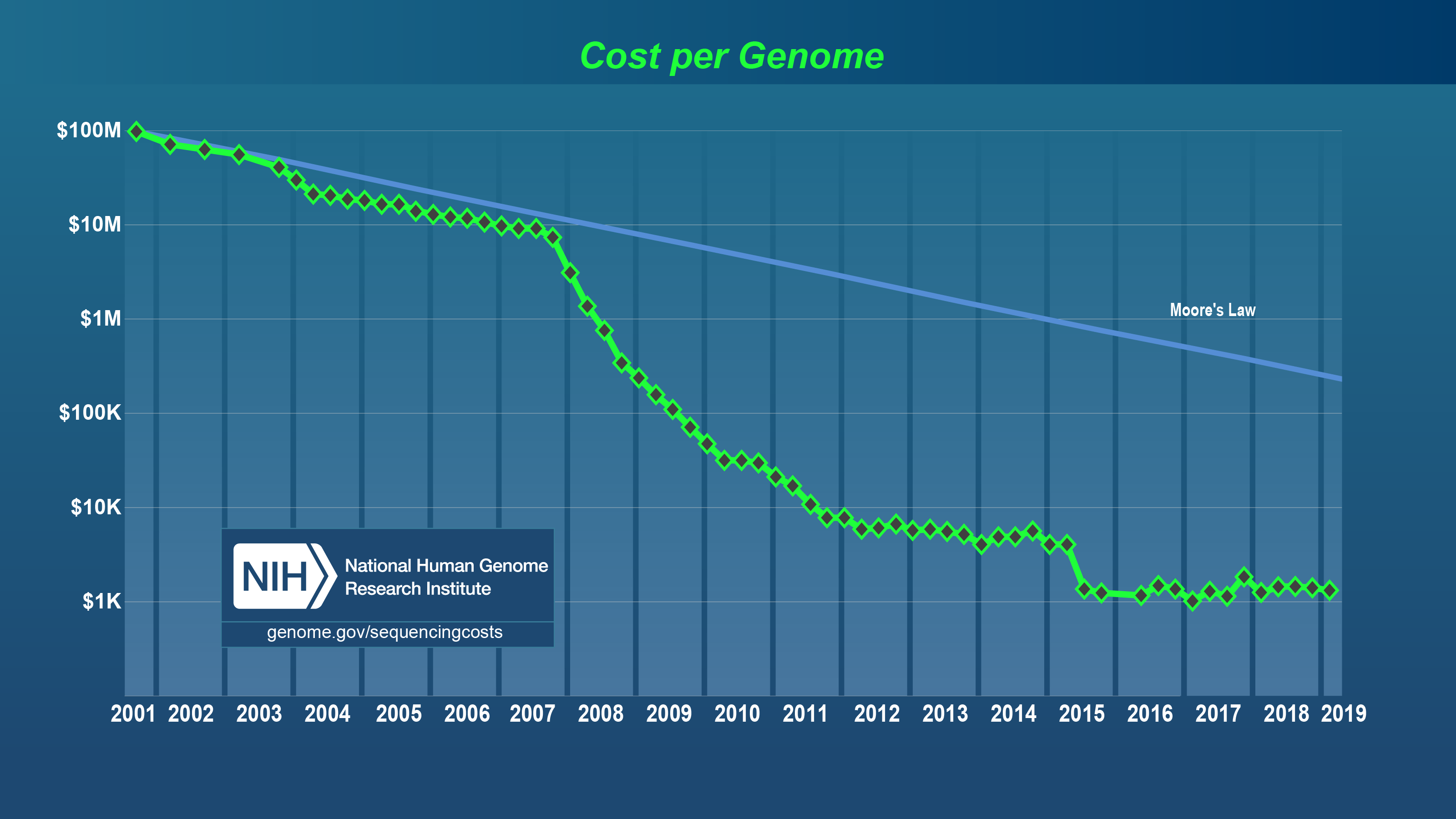

The human genome was sequenced in 2001 by a large consortium of individuals including Craig Venter. At that time it was estimated to cost around $100 million dollars to sequence the 2.91 billion base human genome. The machines that generate sequencing data and associated technology improved exponentially in line with Moore’s law up until about 2008. Moore’s law predicts that computing power will double every 18 months. It was in 2008 that high throughput sequencing appeared at which time, the amount of sequencing data that could be produced by in a single day by a single machine quadrupled (4x) every year. Instead of producing megabases of data, data was being produced on the order of gigabases and Terabases. One lane of Illumina sequencing can generate 300 million 150 base-pair paired reads consisting of 90 billion bases. It is not uncommon today for a bioinformatics project to exceed several Terabytes of raw and processed data. As this trend appears not to be going away anytime in the near future, the need for bioinformaticians to translate this raw data into a format that is informative to a biological problem is greatly needed and will be for the foreseeable future.

Cost to sequence a human genome using a logarithmic scale on the y-axis and year on the x-axis. For more information about this figure see www.genome.gov

Acknowledgements

Some of the funding to produce this workbook was provided by a joint collaboration between Iowa State University and resources provided by the SCINet project of the USDA Agricultural Research Service, ARS project number 0500-00093-001-00-D.